Note: Sandia’s Elaine Raybourn is featured in the first two episodes about the future of work in season two of the Science in Parallel podcast.

Note: Sandia’s Elaine Raybourn is featured in the first two episodes about the future of work in season two of the Science in Parallel podcast.

The pandemic forced many workers into remote-only environments. Now, more than two years after it started, lessons from that imposed shift are reshaping how Department of Energy national laboratories and other computational science employers are structuring jobs and workplaces.

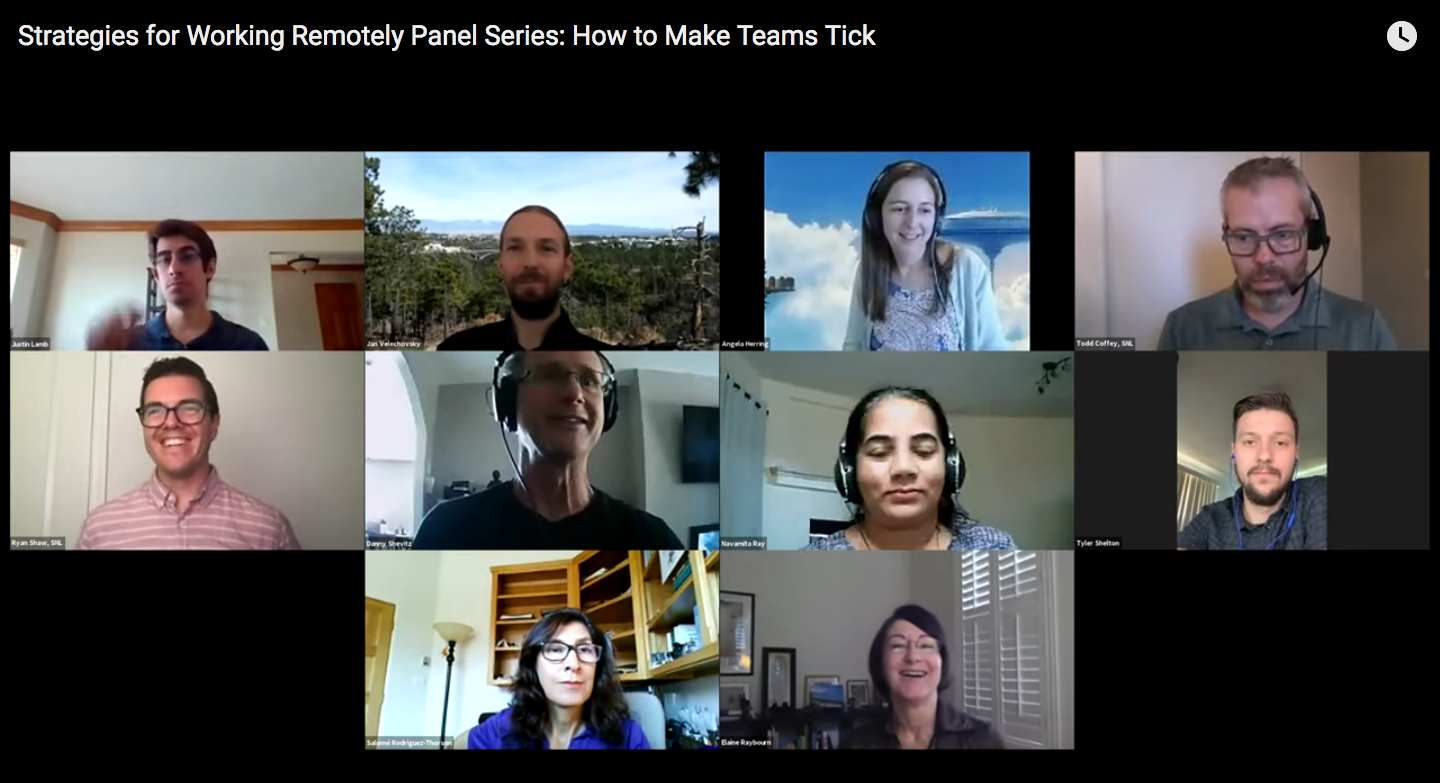

Even large, far-flung teams accustomed to remote work learned to remain connected when it wasn’t possible to travel for in-person meetings. Much of that work came together in online panels called Strategies for Working Remotely, a DOE Exascale Computing Project (ECP) series led by Elaine Raybourn of Sandia National Laboratories.

Raybourn, a social science researcher in Sandia’s Applied Information Sciences Center, has been curious about technology for teams and learning across media for a long time. “What really connects my experience with the whole working remotely topic is my interest in virtuality. When I was little, I always wanted to be in two places at once. And I was always told, actually, you can’t do that. And I never accepted it.”

Now she studies how teams can extend and blend experiences between real and virtual spaces, seeking “a future that we co-create together that isn’t bound by walls.”

Raybourn also is an institutional principal investigator for Sandia’s interoperable design of extreme-scale application software (IDEAS), one of a hundred ECP research groups. IDEAS focuses on teams of teams, software developer productivity, and software sustainability.

Even for a primarily virtual organization like ECP, the shutdown was a shock, Raybourn says. Teams had the organization and tools to do many things remotely in distributed groups, but through early 2020 they still relied heavily on face-to-face meetings “where we could come together, where there could be a lot of innovation, a lot of creativity.” Suddenly the option to travel and meet was gone, and teams moved to electronic communication channels – web conferencing platforms such as Zoom, Teams, BlueJeans and Webex. Those tools became overused, eroding the overall experience.

‘Now we’re going to have to learn new skills.’

Project leaders realized that in shifting to all-remote work, people felt a loss of control and faced steep challenges, personally and professionally. Raybourn could see what was coming. “Now we’re going to have to learn new skills. And not only that, but we’re going to unlearn old habits and old ways of thinking, especially about our expectations for productivity.”

A month into the shutdown, ECP software technology leaders Mike Heroux and Lois McInnes and ECP training and productivity leader Ashley Barker organized a panel featuring speakers who had spent much of their careers working remotely. After serving as a speaker, Raybourn mentioned the communication gap that she’d noticed. ECP had infrastructure for formal communication, training and learning, but the teams lacked an informal communication outlet to build and sustain working relationships now that face-to-face meetings were gone.

Raybourn says building the larger working-remotely panel series was a natural extension of her existing ECP charter: to promote team productivity, with fostering remote informal communication as a key element. “What better way to help the teams be more productive than to provide an outlet where we could have informal dialogue, where they could hear from individual scientists about how they got the science done, about tacit information that normally doesn’t get shared.”

Over the past two years, the series has grown to 13 panels, each carefully designed to be timely and to anticipate the ECP community’s needs. At first, they focused on individual skills, such as establishing a workspace or navigating parenting challenges. The topics evolved toward teams, mentoring and how to bring in new employees. They’ve examined organizational change and hybrid approaches to work.

The panels also covered creativity. “It’s been a real concern that we would not be able to maintain the level of innovation that we need to as national labs,” Raybourn says. For example, many scientists felt frustrated without a whiteboard. The topic arose in several panels as some scientists had brought whiteboards home and either attempted to use them during virtual meetings or displayed them in the background. “My theory is that it’s not the whiteboard, or the artifact, that scientists really miss. It’s the experience that we have at the whiteboard.” More recently, she says, Sandia deployed a digital whiteboard application, but it’s not yet widely used.

Raybourn also notes that the convergence of the pandemic, remote work and a wave of social justice protests has offered an opening to rethink workplace diversity, equity and inclusion. People are more aware than ever of how face-to-face interactions privilege some communicators, whereas others shine at a distance. “With respect to diversity, equity and inclusion, we need to really think about who’s being marginalized when and how can we help so that everyone has that experience of feeling included.”

Unconscious bias, racism, stereotyping, inappropriate language and microaggressions still occur in the workplace, and one’s experience or awareness of any of the above can differ depending on the communication channel. “In using a virtual environment, for example, I may not feel or notice a microaggression the same way I might in a co-located setting, but that may not mean it’s not there.

“And if it is there, we need to do something about it. As we learn more about how technology mediates our communication and experiences, we have an opportunity to unlearn habits that may be harmful to others and be more intentional with our communication.”