About 13.5 billion years ago, the Big Bang filled the universe with ions – atoms bearing electric charges. Intense heat kept every hydrogen atom in that ionic state for a few hundred thousand years, until things cooled enough that each could combine with an electron, creating neutral gas in the so-called Cosmic Dark Age.

“That was before the first stars formed, when there were no photons to see,” says Nickolay Gnedin, a scientist in the theoretical astrophysics group at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois.

After about 100 million years, gravity started pulling particles together and galaxies and quasars began to form. The radiation they produced started ionizing atoms once more, marking the beginning of the Epoch of Reionization. It took about a billion years to turn all the atoms back into ions. “Today, about 98 percent of the gas in the universe is ionized,” Gnedin says.

Little information about these early cosmic times can be observed at the moment, so scientists turn to simulations, combining algorithms with high-performance computing to model the early universe. But bigger telescopes on the horizon – especially NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scheduled for launch in October 2018 – promise more observational data. Over the next five to 10 years, the amount of information from astronomical instruments will increase by tenfold – at least. Simulations must improve to keep up.

“None of the existing models are likely to survive,” Gnedin says. In short, observational data will have more detail than existing computational models.

‘This is one of a few modern cosmological simulation codes.’

As such, scientists must create new models and algorithms that can handle the increase in observational output and then run these simulations on the most advanced supercomputers. Rather than generating dismay along cosmologists, they relish the challenge. “The most significant progress in science took place in fields which had theory and experiment – read ‘observation’ in astronomy – on the same level of sophistication,” Gnedin says. “Pure observational or purely theoretical fields tend to stagnate.”

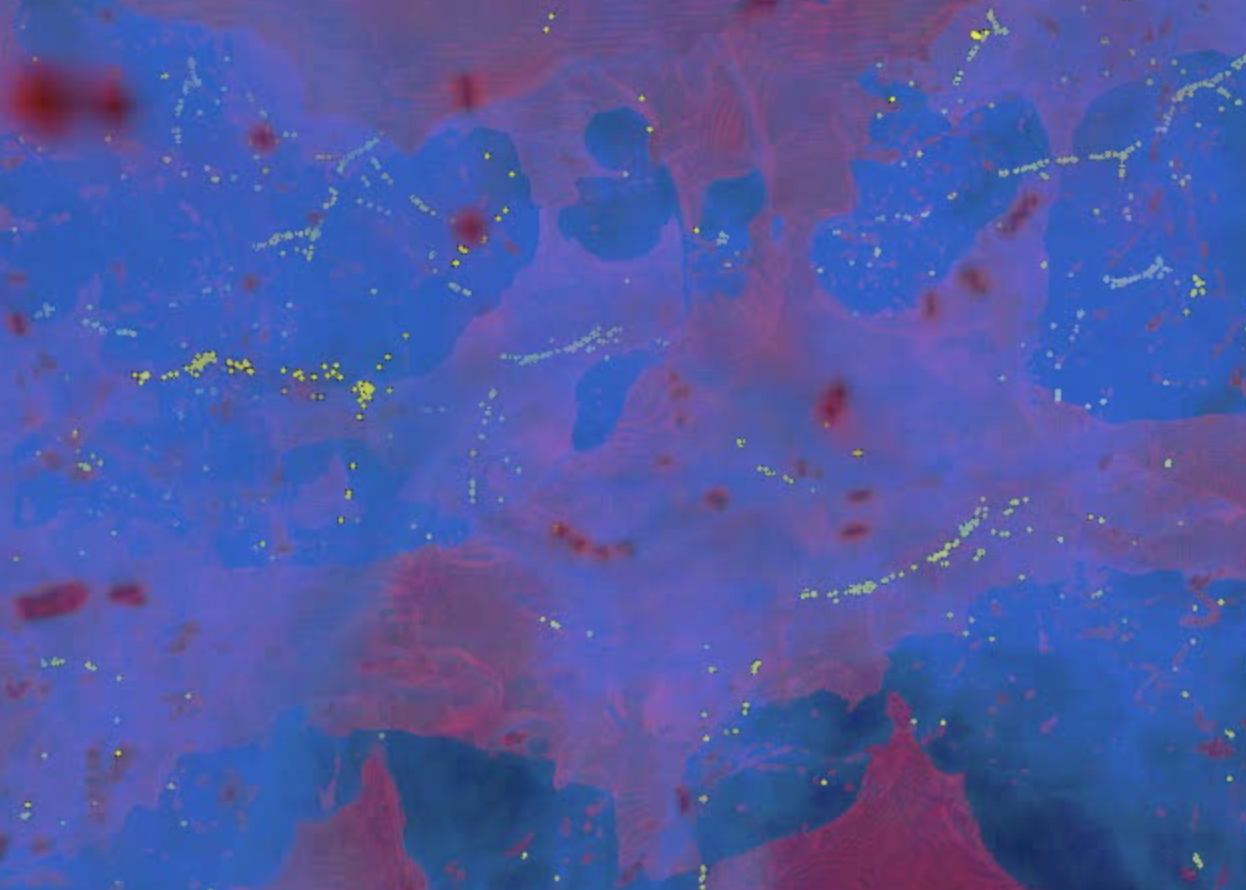

With a Department of Energy INCITE (Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment) award of 65 million processor hours on the Argonne National Laboratory Leadership Computing Facility’s IBM Blue Gene/Q, Gnedin and his colleagues are developing their Cosmic Reionization On Computers (CROC) project. CROC’s main mission, Gnedin says: “to model the signal that telescopes like the JWST will measure, to serve as a theoretical counterpart to the observational program.”

CROC’s model relies primarily on the Adaptive Refinement Tree (ART) code. ART is an adaptive mesh refinement technique that can be used to study the evolution of dark matter and gas. A variety of computer scientists have contributed to this code, starting in 1979.

“This is one of a few modern cosmological simulation codes,” Gnedin says, meaning it was designed to run on the largest supercomputers. ART also can model a wide range of physical processes. More specifically, Gnedin says, it implements a widely used technique that lets a researcher focus computational resources on the most demanding and computationally expensive tasks. “One can think of it as a good manager, reallocating valuable resources to achieve maximal efficiency.”

Teams besides Gnedin’s are developing next-generation cosmic reionization simulations, Gnedin says, and the field is progressing well. “I am very optimistic. When the flood of new data comes, theorists will be ready to compare them with similar high-quality models.” (See sidebar, “Megaparsecs of Progress.”)

Together, the new observations and simulations will provide more precise details of events that drove the creation of our universe. Simulation results will also help scientists understand other aspects of cosmology, from dark matter’s characteristics to the absorption of quasars. So advances in cosmic reionization simulations will expand our knowledge of the universe across time and space.