Note: Sandia National Laboratories’ Mark Taylor is co-author of a paper, “A Performance-Portable Nonhydrostatic Atmospheric Dycore for the Energy Exascale Earth System Model Running at Cloud-Resolving Resolutions,” being presented Nov. 19 at SC20.

How stable will the Antarctic ice sheet be over the next 40 years? And what will models of important water cycle features – such as precipitation, rainfall patterns, and droughts – reveal about river flow and freshwater supplies at the watershed scale?

These are two key questions Department of Energy (DOE) researchers are exploring via simulations on the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM). “The DOE’s Office of Science has a mission to study the Earth’s system – particularly focusing on the societal impacts around the water cycle and sea level rise,” says Mark Taylor, chief computational scientist for Sandia National Laboratories’ E3SM project. “We’re interested in how they will affect agriculture and energy production.”

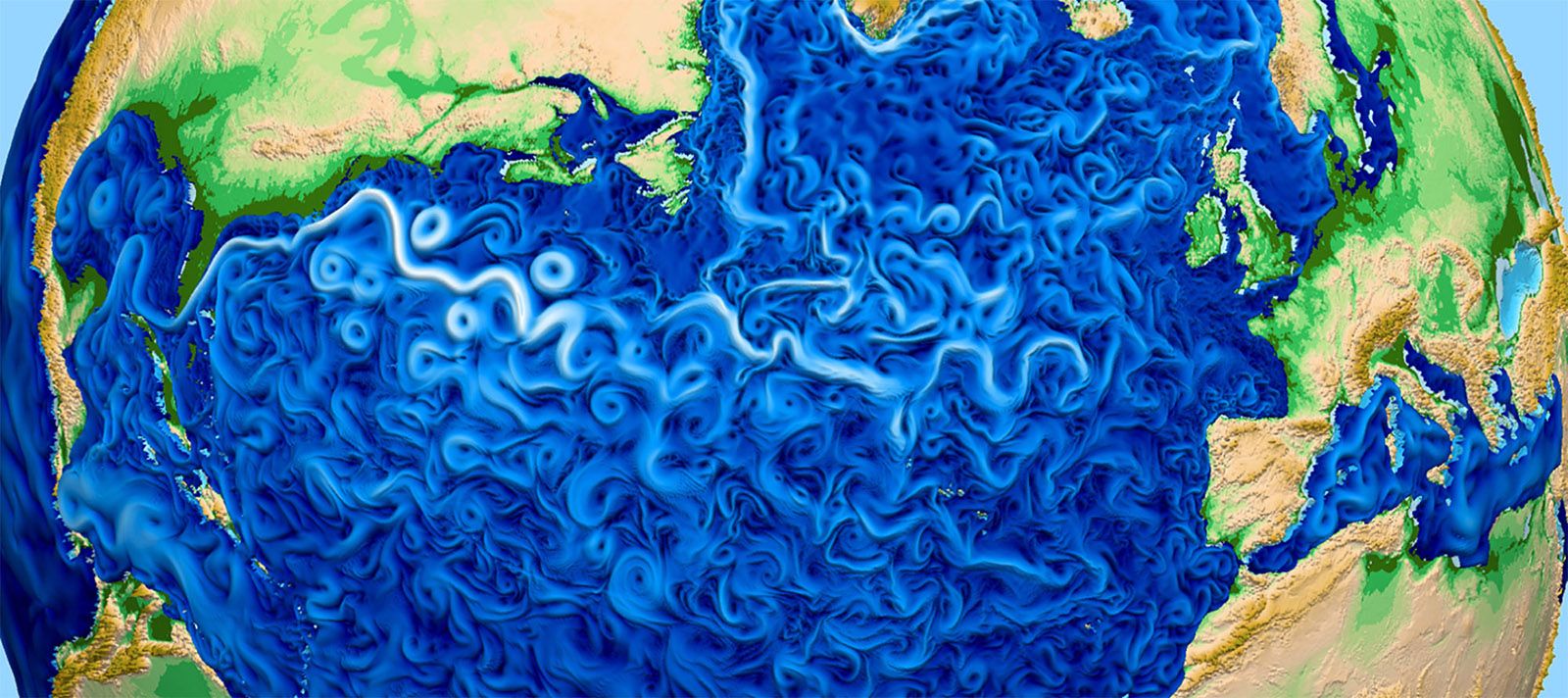

E3SM encompasses atmosphere, ocean and land models, plus sea- and land-ice models. “It’s a big operation, used by lots of groups of scientists and researchers to study all aspects of the climate system,” Taylor says.

“Big operation” describes most climate system models and simulations, which often require enormous data-handling and computing power. DOE is tapping exascale computing, capable of a quintillion (1018) calculations per second, to help improve them.

“The DOE wants a model to address their science questions,” Taylor says. “Each of the different models are big in their own right, so this whole process involves a lot of software – on the order of one million to two million lines of code.”

DOE is building two exascale computers– one at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the other at Argonne National Laboratory – and they’re expected to come on line for research in 2021. They will be among the world’s fastest supercomputers.

Taylor is a mathematician who specializes in numerical methods for parallel computing, the ubiquitous practice of dividing a big problem between many processors to quickly reach a solution. He focuses on the E3SM project’s computing and performance end. The move to exascale, Taylor says, is “a big and challenging task.”

The Sandia work is part of a DOE INCITE (Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment) award, for which Taylor is the principal investigator.

The original Community Earth System Model (CESM) was in the Fortran programming language for standard central processing unit (CPU) computers and developed during a decades-long collaboration between the National Science Foundation and DOE laboratories.

‘We’re pushing the resolution in the calculations up so we can resolve the processes responsible for cloud formations and thunderstorms.’

“To get to exascale, the DOE is switching to graphics processing units (GPUs), which are designed to perform complex calculations for graphics rendering,” Taylor explains. “And since most of the horsepower in exascale machines will come from GPUs, we need to adapt our code” to them.

So far, code is the biggest challenge they’ve faced in the transition to exascale computing. “It’s been a long process,” Taylor says, that includes developing a new programming model. “During the past four years, we’ve converted about half of the code, “rewriting some of it in the C++ language. and using a directed language called OpenACC for another program.

The effort, Taylor adds, requires about 150 people, spread out over six laboratories.

Another challenge: “We wanted to figure out which types of simulations are better for traditional CPU machines,” he says, “because we really want to use the new computers for things that we couldn’t do on the older computers they’re replacing. Some things are ideally suited for CPUs, and you really shouldn’t try to get them to run on GPUs.”

It turns out that tasks like simulating clouds work best on GPUs. So he and his colleagues are creating a new version of a cloud-resolving model. “We’re pushing the resolution in the calculations up so we can resolve the processes responsible for cloud formations and thunderstorms,” he says. “This allows us to start modeling individual thunderstorms within this global model of the Earth’s atmosphere. It’s really cool to see these realistic models of them developing – simulated on a computer.”

Exascale power will help researchers simulate and explore changes within the hydrological cycle, with a special focus on precipitation and surface water in mountains, such as the ranges of the western United States and Amazon headwaters. It also should help with a study of how rapid melting of the Antarctic ice sheet by adjacent warming waters could trigger its collapse – with the global simulation to include dynamic ice-shelf/ocean interactions.

DOE’s ultimate goal for E3SM is to “advance a robust predictive understanding of Earth’s climate and environmental systems” to help create sustainable solutions to energy and environmental challenges. The first version of E3SM was available for use in 2018. The next is expected to be ready in 2021.